Alberta’s Duck Hawks

A “Cliff Notes” Story

February 2024

Just over a century ago, a Palisades resident recorded the activity of local falcons in her diary. This was only a small moment in Alberta Miles’ relatively long life, but it can help us learn more about these special animals — which vanished for decades, but have since returned to their cliffs.

(1861–1925)

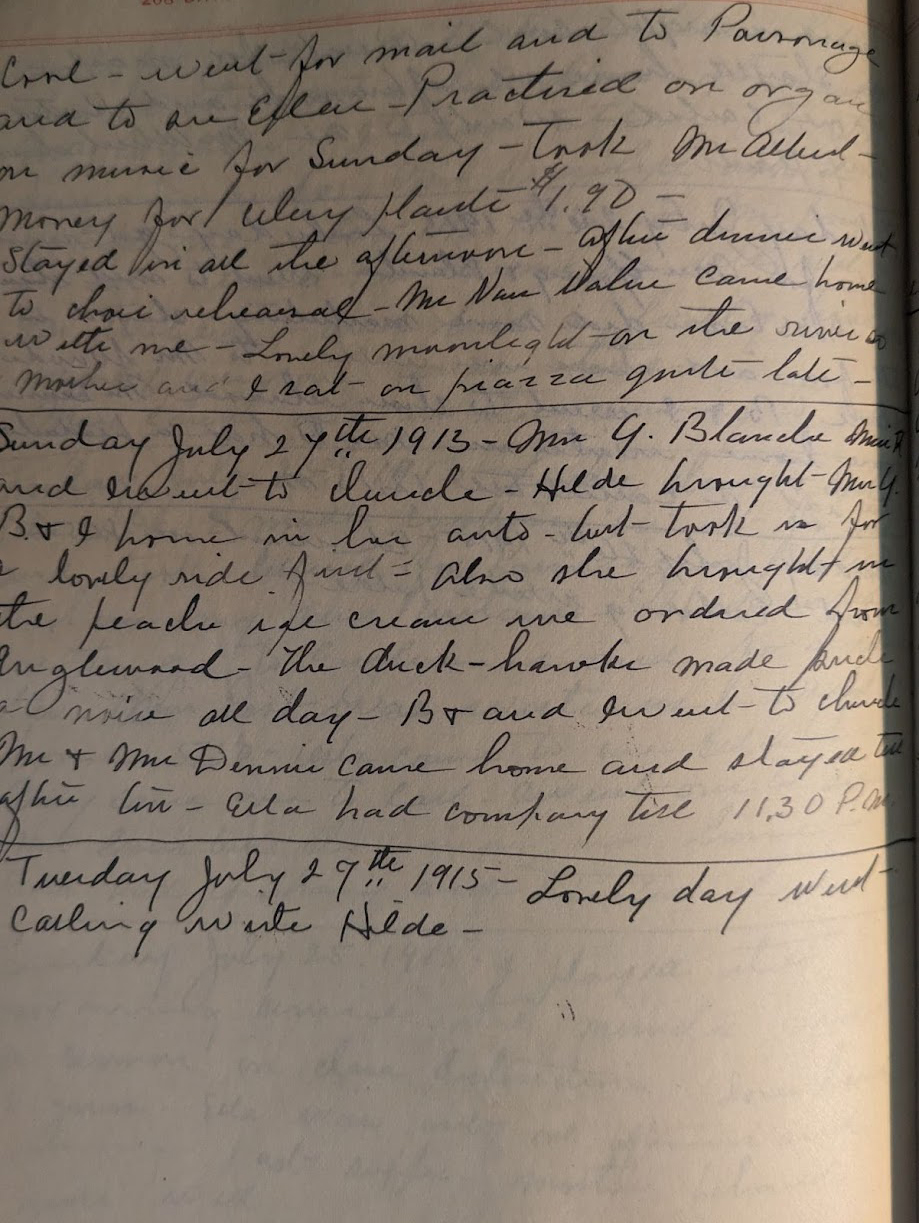

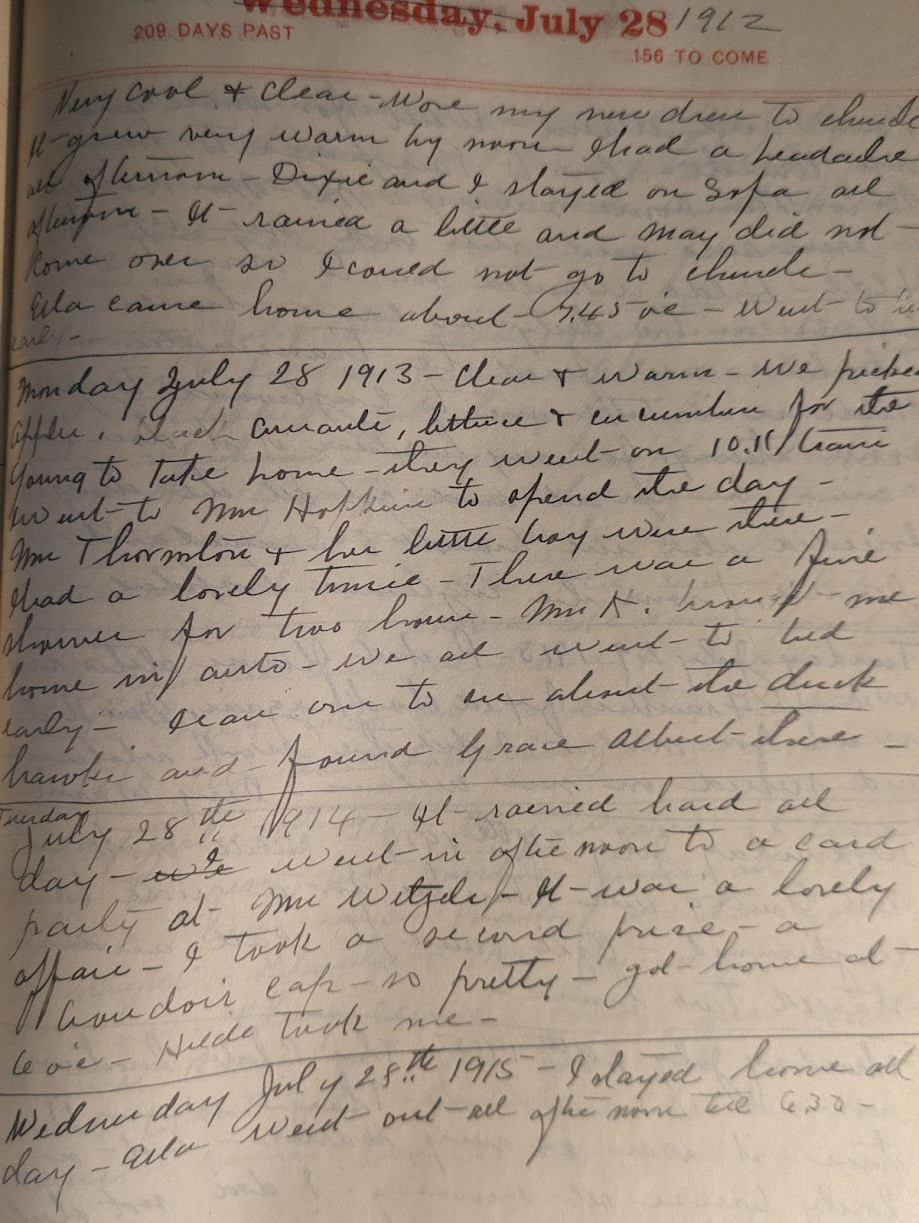

On Sunday, July 27, 1913, Alberta wrote,

The duck-hawks made such a noise all day.

Here, Alberta is using the term “duck hawk,” which is an old American name for the peregrine falcon. These birds are fearsome predators, often going after domestic pigeons, blue jays, and waterfowl (hence the name “duck hawk”). Their choice of prey and their tendency to nest on steep ledges make them ideal for urban settings, where tall buildings and bridge towers can take the place of natural cliff faces.

Though falcons are known to nest within New York City and the greater Metropolitan Area, the Palisades is once again home to several breeding pairs who prefer the rustic life. It is no surprise Alberta Miles saw her duck hawks in 1913, either. Like the birds she wrote about, Alberta’s “nest” — the estate her family called home — was directly atop the Palisades Cliffs. From this lofty height, she could see across the Hudson to Yonkers and all the way to Long Island Sound beyond. Her father, industrialist Col. Sweeting Miles, who operated a large mill on the riverfront in Alpine, had the family mansion built during the 1860s. Her beloved father died in 1909, leaving Alberta to care for her aging mother. She was 52 years old when she noted the “duck hawks” in her diary. As an heiress, she did not have to earn a livelihood like others in her community. She instead dedicated much of her time to the Alpine Methodist Church. She was a skilled organist, lending her talents to the regular Sunday services, as well as at funerals (and even a memorial to those lost on the RMS Titanic the year before). She was the Choir Director and Treasurer for the church, and by all accounts was much loved by the congregation.

And one day in July, the falcons who nested right on her cliff face were making such a racket it interrupted her schedule. In the mid-summer, peregrine chicks begin to fledge: they leave the nest and start to fly. Even today, during this time of the year park employees often hear the familiar squawks of these apex predators as their families swell with activity, the young birds sparring with one another in the sky, learning their craft.

The next day (July 28, 1913) Alberta wrote,

I came over to see about the duck hawks and found Grace Albert there.

Painting a familiar scene, Alberta and her friend Grace are looking over the Palisades Cliffs to get a glimpse of the little falcons making “such a noise.” More than a century later, locals still crowd along the viewpoints at State Line Lookout and other overlooks in the park to see our raptors in action.

Peregrine falcons are among the most widespread birds in the world. But even with their great adaptations and hunting prowess, nothing could prepare American peregrine populations for DDT pollution of the last century. Succumbing to contamination, these birds vanished entirely from the East Coast, and remained endangered elsewhere during the 1960s. They disappeared from the Palisades as well. Throughout the next few decades, movements to ban harmful chemicals and establish captive breeding programs gave the species new hope for survival. Today, peregrine falcons once again roost on our cliff edges — endangered no longer.

Their modern name, “peregrine,” comes from the Latin for foreigner or pilgrim, and could refer to the falcon’s habit of migrating seasonally. Every year from September through November, citizen scientists gather at State Line Lookout to keep count of the species that are flying south. Among the thousands of raptors they count are many peregrines from our north.

Our breeding pairs tend to stick around through the winter, and some have become famous in the local birding community. Unfortunately, one female peregrine who had been the star for the past few years seems to have vanished. Her mate-for-life has dutifully posed for photographs alone, but she has not made a reappearance. Other females seem to be scouting out the territory, sounding with calls of their own. Though it is sad to say goodbye to a raptor that has impacted so many, we are hopeful for the next generation of peregrines to move in. What we can learn from Alberta’s small note in 1913 is that breeding pairs might change over time, but the species will always have a haven along the Palisades (and a fan club!).

Today, you can have the same experience Alberta Miles did from her clifftop estate so long ago. Visit our park, keep your eyes out, and you might meet our noisy feathered residents!

– Francesca Costa –