“Alphabet Soup”

A “Cliff Notes” Story

November 2004

“Alphabet Soup” was one of the phrases used — by supporters as well as detractors — to describe the sometimes bewildering array of acronyms used for Franklin Roosevelt’s various “New Deal” agencies during the Depression years: there were the CWA and the WPA; the CCC and the NRA; the FSA and the SSA; not to mention the good old TVA. If people at the time found these acronyms confusing, who can blame us decades later if we sometimes stumble over them as well? But three of these agencies played a profound role in shaping the park as we know it today. We thought it might be a fitting tribute at the close of this particular year — the seventieth anniversary of the major start point of their labors in the park in 1934 — to offer a brief breakdown of the individual agencies involved and to highlight some of their accomplishments here in the Jersey Palisades.

Some back story will be helpful. The start of the Great Depression of the twentieth century was marked by the stock market crash of October 1929. Over the next three years, as the economy sank to frightening and unprecedented depths, the federal government, under Herbert Hoover, remained reluctant to play an active role in reversing the decline. Instead, they relied on state and local agencies to handle the immediate crisis, even as the unemployment rate in many areas climbed to 25 percent. The park found its budget slashed, and so turned to these local agencies for assistance. Through November and December 1931, the Bergen County Unemployment Survey Committee placed about 500 men in day-job positions in the park; in 1932, the park’s Annual Report noted,

A critical condition in the Park, due to the lack of funds with which to employ labor, was solved in part by arrangement with the New Jersey State Emergency Relief Agency. The Administration, with the cooperation of the Bergen County Director of Emergency Relief and the municipal directors in several Bergen County cities, assigned to work in the Park groups of 50 men, released for that purpose from municipal projects. During the month of December, these groups of men were drawn from Hackensack on daily shifts. The City provided the men with luncheons and paid them in food orders. The Commissioners [of the Palisades Interstate Park] paid the cost of transportation, premium on Workmen’s Compensation Insurance, which was taken out in the name of the City, and gave the men hot coffee and cigarettes.

The Report also noted that “many permits were issued to unemployed persons, citizens of New Jersey, granting the privilege of cutting and collecting dead or fallen timber, at designated locations, for personal use as fuel.

In November 1932, Roosevelt was elected president; after his inauguration the next year, he would begin to develop what became known as the New Deal, which represented a much more aggressive federal approach to the crisis. Through most of 1933, as those plans were being drawn in Washington, the park continued to rely on local agencies such as the County’s Emergency Relief Bureau and the State’s Emergency Relief Administration, which together provided all standard maintenance in the park, with regular paid staff — down to a skeleton crew from a few years earlier — serving as foremen and providing services on Sundays and holidays. Throughout the year, the local relief agencies provided a total of 6,855 man days (which at $4 per day, amounted to $27,420 worth of labor for the park).

By December 1933, the New Deal began to kick into gear. In that month a Civilian Conservation Corps camp was constructed at what is now Greenbrook Sanctuary; it was occupied in January.

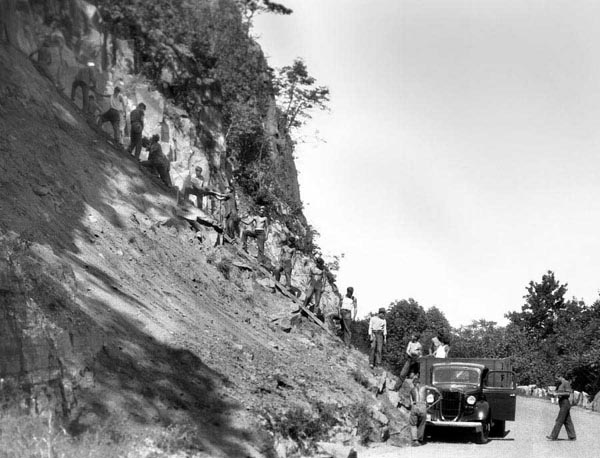

The “CCC boys,” or just “CCCs,” as they were known across the country (eventually over 2 million young men participated in the program), were supposed to be between 18 and 25 years old, though based on interviews with several veterans of the group, it was not uncommon for younger men to obtain fake IDs to join. They lived in army-like camps where, in addition to performing public works projects, they were fed and clothed and received training and drill instruction. They were paid $30 per month, $25 of which was sent home to their families. For the next several years, this group, eventually supplemented by a second CCC camp also at Greenbrook, built thousands of cubic yards of retaining walls running above Henry Hudson Drive. The teenagers broke the stone into size with picks; they built wooden slides up the slope; they hauled the rock up those slides with block and tackle and the muscles in their backs. They were supervised by former army officers, many of them southerners, most of them tough as nails. No injuries were reported during this work.

Over the next decade, the CCCs of the Palisades also planted thousands of trees and killed millions of tent caterpillars; they built stone picnic tables (like the retaining walls, many still in use) and helped prevent and fight forest fires in the park.

A second agency that arrived on the scene in December 1933 but swung into full gear the following year was the Civil Works Administration, or CWA. This was a temporary agency Roosevelt was able to get chartered by Congress through March 1934. Unlike the CCC boys, these men lived nearby and commuted to their work assignments. In its several months in the park, the CWA would leave an impressive legacy. Work began in January on the Alpine Bathing Pavilion (still in use as Alpine Pavilion) and the adjoining refreshment stand (now used for storage and as a catering facility); an underpass for the Lambier trail beneath the Henry Hudson Drive (the trail is now closed, but hikers still find the underpass); a bathhouse and refreshment stand at Bloomer’s Beach (both still standing, though no longer in use); numerous concrete picnic tables; two large trash incinerators (the park no longer uses these); numerous smaller trash burners (also no longer used); and other projects. For the two bathhouses, besides using massive stone boulders for their construction, the CWA workers had to dig out the septic fields for these — by hand! By the agency’s termination on March 31, 408,403 man hours had been logged in the park, and most of the projects were near completion. The projects were finished by the State Emergency Relief Administration, and the facilities were open by Memorial Day.

The third New Deal agency to leave its mark on the park was perhaps the best known of all, the Works Progress Administration, or WPA, which would over its decade of existence employ over 8 million men nationwide. Here in the park, WPA workers, who like the CWA workers lived at home and commuted to their assignments, built a couple of dozen rustic cabins at Ross Dock (these were abandoned during World War Two and eventually torn down); they built “Lookout Inn” at State Line Lookout (still in use); and they constructed the walls along the lookout point there. They also performed numerous road repair and regular park maintenance projects through the early 1940s, and they built bridle paths (now our ski trails at State Line) and dizzying stone stairways up the mountainside (still used by hikers every day). The program was finally disbanded during the war. In addition to labor, the WPA also provided skilled services to the park, including engineers and surveyors who laid out the original course of the Palisades Interstate Parkway (built in the 1940s and 50s). WPA crews also demolished many of the mansions and other structures along the proposed route of the Parkway. And they photographed it all.

This, of course, is just a thumbnail description of three New Deal agencies that worked in the park and some of the projects they accomplished. The full story could very easily fill a book — though it is a book, sad to say, that can probably never be written properly at this late date: even the youngest of the CCCs, those who lied about their ages to get in, are old men now. Every year there are fewer of them. The New Deal was — and remains to this day — politically controversial. But here in the park, the legacy of the individual men and boys who participated in those agencies — a legacy left for all to see in silent stone walls and buildings — can still cause us to stop and wonder. Who were you?

And where did you go from here?

– Eric Nelsen –