Cliff Dale (Part II)

A “Cliff Notes” Story

January 2008

In the Park Commission’s Annual Report for 1939, two pages are devoted to the accomplishments of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in the park that year, ending with, “The razing of the Zabriskie house on the edge of the cliffs in Alpine, one of the properties conveyed to the Commission by John D. Rockefeller, Jr., was partly completed. This is one of the buildings visible from the river that has had to be demolished in compliance with the terms of the gift, with a view to the preservation of the skyline of the Palisades.”

Rockefeller had purchased this particular piece of property in 1930. In 1933 he donated it, along with many similar properties he’d acquired around the same time, to the Park Commission, with the request that the Palisades skyline be returned to its natural appearance. This was in response to fears that the construction of the George Washington Bridge, which opened in 1931, would lead to a spate of over-development on the cliff top, marring the Park Commission’s thus-far successful efforts to preserve the Palisades scenery.

And so the mansions fell.

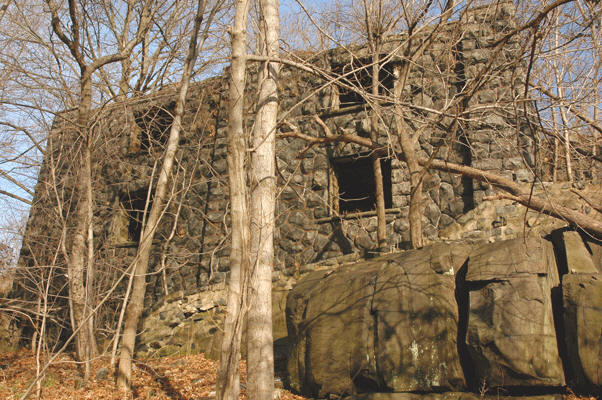

Except, this particular mansion, once the largest on the cliffs, did not fall so easily. A sizable piece of it, seven decades later, is still standing. Built into a hillside, the southern portion is two stories tall; north of that, the WPA crew must have finally decided to use the basement as a containment vessel for the thick-walled upper stories they toppled. Around the west side of the foundations, in numerals formed by stone and mortar, about two feet tall, is a date:

1911

George Albert Zabriskie was forty-two years old in 1911, the scion of a family tree that traced its New World roots back to August 1662, when 24-year-old “Albert Saboriski,” probably of Prussian or Silesian descent and seemingly traveling alone, first stepped off D’Vos (The Fox) at the docks at New Amsterdam. Albert would eventually cross the Hudson into New Jersey. The family he began there would become among the most prominent in Bergen County by the time of the Revolution. Throughout the nineteenth century, the family continued to grow and flourish. George A. Zabriskie was born to a branch of the family that had re-crossed the Hudson to live in New York City. By the time he was supervising the construction of a cliff-top summer estate in Alpine — his year-round residence was on Central Park South — Zabriskie had made a name for himself in the flour business, serving as the New York representative for the Minneapolis-based Pillsbury flour mills.

The fifteen-room manor house that was built for Zabriskie at Alpine in 1911 was constructed of native stone on a 25-acre estate that had once belonged to William C. Baker, an innovator in using steam heat to artificially incubate chicken eggs. (Over 200,000 chickens a year were hatched in buildings on Baker’s estate — see our previous featured story). In addition to the manor house, Zabriskie had a gate house built on the Boulevard (today’s U.S. Route 9W), where he and an aunt, who lived with him for many years, stayed during the construction of the manor house. In the natural hollow to the south of the manor house was a man-made pond. Terraced gardens adorned the cliff edge to the east. On the other side of the road were cottages, greenhouses, a barn, and other buildings (the Alpine Public School stands on these grounds today). Zabriskie kept the name that Baker had assigned to the estate, “Cliff Dale” (though he usually spelled it as one word, “Cliffdale”).

During World War I, Zabriskie was named sugar and flour administrator of the Food Administration Board under Herbert Hoover and a member of the United States Sugar Equalization Board. As noted in the New York Times, “His wartime and post-war work on behalf of the welfare of America’s allies won him the awards of the Belgian Order of the Crown, the Polish Polonia Restituta Cross, and the Order of Icelandic Falcon.”

But his true passion was for American history and historic preservation. A member of the Sons of the American Revolution, Zabriskie would go on to become a president of the New York Historical Society. From the Times again: “Active in patriotic societies and civic affairs of New York, [Zabriskie] was chairman of the membership committee of the Museum of the City of New York. He often fought to prevent the destruction by city planners of historical landmarks, such as the old Fort Clinton in Brooklyn.”

Zabriskie wrote a number of books, some of them self-published, on topics ranging from polar exploration to early Dutch Christmas traditions to The Bon Vivant’s Companion, a guide to mixing cocktails.

After he sold his Alpine estate to a real estate agent working for Rockefeller, George Zabriskie continued to lead an active life, pursuing his many and eclectic interests. He was eighty-five years old when he died at his winter home at Ormond Beach, Florida, at the start of 1954.

Today, the ruins of his cliff-top estate continue to captivate and intrigue hikers.

– Eric Nelsen –