The Making of a Hut

A “Cliff Notes” Story

February 2003

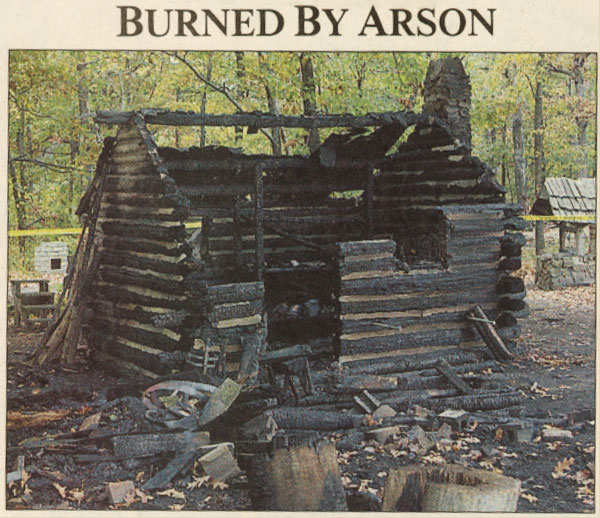

Two years ago here, we told the sad story of how the “soldiers’ hut” at Fort Lee Historic Park, which played an integral role in the school programs there, had been burned down by arson. Following an outpouring of support from the community, this past fall the hut was rebuilt. Staff photographer Anthony Taranto was sent to document the construction process — and ended up being an active participant in the work…

A couple of weeks before the building was to begin, I stopped at the Historic Park to scout out the site. By coincidence the first delivery of logs arrived at the same time I was there, which gave me a good insight into the scope of the project. The truck had at least two dozen logs on it, each log about twenty feet long. I had an idea of what the finished project would look like, but none about how we were going to turn these logs into it.

When the building was set to begin, I met Roland Cadle, who had been hired as a consultant and main builder. Roland is from Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania, where he is a pastor. For thirty years he has also been building log structures of the Revolutionary War period, using traditional techniques. Besides Roland and the Historic Park staff, a number of volunteers assisted us throughout the project.

The first day of construction was comprised mostly of measuring and picking out the best logs. We needed to find the straightest possible logs, meaning those without “doglegs” or bends in them, keeping in mind that the fattest logs would be used for the base, with thinner logs to be used near the top of the structure.

The plan was to build the new hut around the existing chimney. (This proved to be more of a difficult task as the project went along, because we had to customize the logs to fit around the chimney; it would be more typical to build this kind of structure first, and then fit the chimney to it.) All the tools and techniques used would be authentic to the time period, with two exceptions. A chainsaw and a power drill would make up for limited manpower and time. Otherwise, the main tools to be used were axes, draw knives, and tie carriers.

After the logs were selected, we de-barked them, using the draw knife. This work would continue throughout the project, while other work was going on as well.

The real skill came in the “steepling” and notching of the logs, techniques which were used in their placement. As I quickly learned, this was not a matter of building “Lincoln Logs” on a large scale. The notches in the logs would be carefully “steepled” to lock into one another.

This work, the notching and steepling, was done by Roland, and only by Roland. Throughout the project, my respect for Roland’s ability to handle the axe grew immeasurably. It’s one of those things that seem simple because when you think of an axe, you think perhaps of splitting or chopping firewood — rough work. In Roland’s hands, the axe’s use could be described as delicate, a sculptor’s tool. And like any master craftsman, he made it look easy. As though it were no big deal consistently to hit the exact same spot on a log, using exactly the right amount of force, with a 15-pound axe. The rest of us helped do the basic rounding of the log ends, in order to “disguise” our use of the chainsaw.

(If our axe-work was sloppy, which it always was, Roland would tell us that it looked like a beaver had chewed down the tree…)

Once the walls were in place, the door and window portals were cut out, and these items installed.

The truly grueling work came as the hut got taller, and logs had to be rolled into place above our heads. Especially, of course, when building the roof, because logs had to be hoisted on our shoulders and brought to the desired height on ladders. The hut may seem small when you just look at it, but not so when you’re placing a couple of hundred pounds of log at the roof’s apex.

The most time-consuming part of the process was “noggening” — filling the gaps between the logs with split wood — and “chinking” — covering the split wood with a mud-like mortar. You don’t realize how many gaps, crevices, and holes there are in a log house until you set out to place mud into all of them with your hands. Still, with winter coming on, it must have seemed like time well spent to a soldier planning to live in such a structure.

Stepping back to look at the nearly completed hut one day, Roland reminded me that eight to ten soldiers might have lived in such a structure. And that while these soldiers lived in their hut, they would have been at work building a structure more than twice its size — to house a single officer.

– Anthony Taranto –