Some Paint, Some Mortar, a Couple of Mops and a Bucket of Water

A “Cliff Notes” Story

September 2003

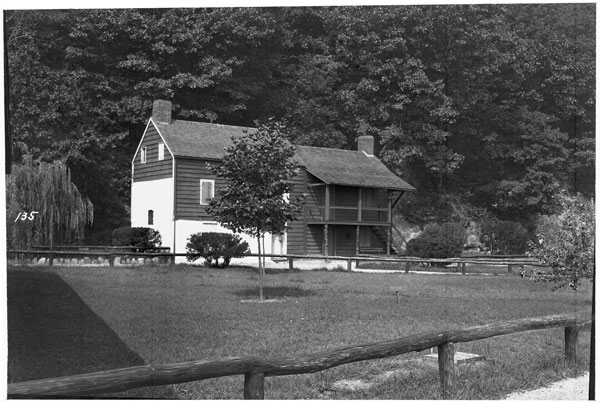

Frankly, this is the article we hoped to publish in the last issue of our visitor’s letter. We hoped then to be able to tell our visitors that the Kearney House was looking the best it had in decades, and that they should make a point of getting down to the Alpine Picnic Area on the Hudson to take a look. Unfortunately, when our end-of-June deadline rolled around, the house was looking far worse than it had — probably in a century or more…

As anyone in the Northeast who wasn’t asleep for the past six months can attest, the weather has been miserable. And that was the problem. A major exterior restoration project that was scheduled to be finished by our normal opening time in May had gotten hopelessly behind schedule. This wasn’t the usual delays you expect with any kind of project of this sort, where supplies are late in arriving or that kind of thing. This was months behind schedule, and the house, when we were finally able to open it at all for the July 4th weekend, looked like a disaster. The clapboards were stripped to bare wood, and much of the mortar between the stones had been chipped out, but not yet replaced. Yellow tape blocked off the back, where ladders and such were being stored, giving it the feel of a crime scene. And so we asked our summer staff to write about something — anything — else, and we got their excellent article about wild turkeys instead.

The project had been in the works for a year or more, the result of our collaboration with the New York City architectural firm of Page Ayres Cowley, LLC. The talented staff at Cowley had developed a plan for restoring the house’s exterior to something like its original form, using a scientific approach. They took paint and mortar samples from various places around the house and analyzed them.

We learned from these analyses that there were up to a dozen layers of paint on the clapboards — and, unfortunately but not surprisingly, that some of the earlier layers were lead-based. Under a microscope, the paint layers can be looked at almost like tree rings, and comparing them with photographs, we were able to date many of them. We had the fresh coat put on the house in 1909, when it was to serve as the centerpiece of a dedication ceremony for the new Interstate Park. We had the bizarre layer of “bottle green” that was applied around 1930 — then promptly painted over white again a year or two later. Right after this last layer of white, a mystery: a layer of fine rock dust between it and the next white layer, which was applied by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the late 1930s. (We think we’ve figured out the rock dust, that it was probably from the construction of the nearby stone picnic pavilion and refreshment stand, built by the Civil Works Administration in 1934.) And then there are more layers of white. The earlier shades of white, the ones that preceded the 1909 paint job, would be matched for the new coat of paint we would apply. Likewise, an early shade of dark green would be applied to the trim, as it probably had been in the nineteenth century.

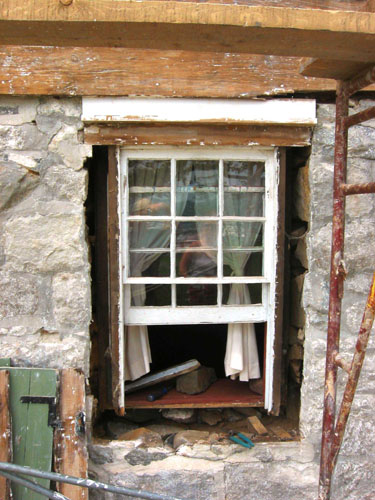

From the mortar analysis, we got confirmation that the interior mortar, that which was actually used to hold the foot-and-a-half-thick stone walls together, was, as we had suspected, Hudson River mud. An outer layer of light-colored limestone-based mortar was applied to the edges. New mortar would be custom made to match the limestone “recipe.” And the paint that had been applied to the stone walls in the past few decades would be removed — and would stay off.

The paint removal had to be done by a firm licensed for lead paint abatement, Niram, Inc., of Boonton, New Jersey. Niram would use the gentlest means possible, chemical strippers that would not harm the substrate. Unfortunately, these chemicals need to be applied in relatively warm, relatively dry weather. So when our May opening day came, the house was still surrounded by yellow tape, and a crew of men in respirators was busy applying a chemical that temporarily had turned the stone section of the house a sickly green color. Weeks dragged on before the next set of contractors — Fame Construction of Great Neck, New York, who would repair damaged clapboards and sills, prime and paint the wood, and re-point the stone walls inside and out — could begin.

But once they got to work — and when the weather wasn’t too bad to stop them — Fame’s progress was impressive, and as July moved along, each day the house looked a little bit better, a little bit more like a home. Until finally, there came an afternoon when several of us who have known the house for years could only stop and stare. It had become beautiful! More beautiful than any of us could remember.

Then it was our turn. As anyone who has had construction work done in her or his home knows, no matter how careful the workers try to be, the place is a mess when they leave. So it was time to get out the mops. We decided to begin in the attic and work our way down. To judge from the layers of dust up there (and no, we didn’t analyze them), we may have been the first people to attempt this in a thorough fashion since — we don’t even want to think about it. Two whole days in the tight quarters there, however, and it seemed like a new place. Then, with some volunteer help from Girl Scout Troop 161 of Dumont, we took on the rest of the house.

Before-and-after photos by Anthony Taranto.

And so now, in this issue of our visitor’s letter, we can say it. The Kearney House is looking the best it has in decades, and you should try to make a point of getting down to the Alpine Picnic Area on the Hudson to take a look. We’re open weekend and holiday afternoons. We’re still waiting on some gutters (this is a material delay, the kind of thing you expect with this sort of project).

But they’ll go up soon enough.

– Eric Nelsen –